The History of the Chicago White Sox - Part 10

The White Sox of the eighties saw two major developments. The first, and the more complex one, is the team’s play on the field.

Back in 1976, the year before the South Side Hitmen, the Sox were baseball’s second worst team, finishing with a record of 64-97. Because of a rule that, in retrospect, is completely ridiculous, the first overall pick in the MLB draft had to go to an American League team and a National League team in alternating years. In odd numbered drafts, the worst AL team got the first pick. In even numbered drafts, the worst NL team got the first pick. This system ensured that the White Sox, who finished with a .398 win percentage, got the first pick in the 1977 MLB draft over the NL’s Montreal Expos, who had a win rate of .340.

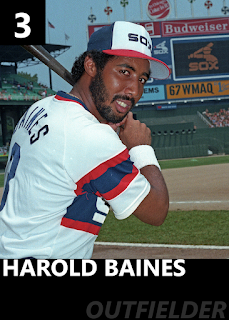

With the first pick in the 1977 MLB Draft, the Chicago White Sox selected Harold Baines.

Baines wasn’t an all-time great like Minoso, Appling, Lyons, or even older players like Doc White and Ed Walsh, but he was an incredible player. He was the one to lead the team back to something that resembled sustained success. From the ending of the go-go era to Baines’ rookie year, the Sox had three winning seasons in 12 years. They were rarely able to win, and when they did, they couldn’t keep their guys around for the long haul.

Starting in 1981, with Baines in his second season, the Sox would go on to have five winning seasons in seven years. This success came alongside superstar catcher Carlton Fisk and pitchers LaMarr Hoyt and Tom Seaver. Manager Tony LaRussa quickly became one of baseball’s best, and it all came together in 1983, when the White Sox went to the playoffs for the first time. It certainly took them long enough. The playoffs had existed since 1969, and the Sox, who certainly would have made it multiple times in the go-go era, had been either non-competitive or mediocre for all its 14-year existence.

The atmosphere around Comiskey Park in the eighties was the best it had been in years, even better than the ‘77 season. Attendance in 1983 broke two million tickets sold in a season for the first time in team history. Nancy Faust was conducting crowds, and the stadium, which was over 70 years old by this point, was still as strong and loved as ever.

Baines and Fisk’s White Sox walked into the 1983 ALCS to face Cal Ripken Jr. and Eddie Murray’s Baltimore Orioles.

The Sox edged out a win in game one behind LaMarr Hoyt’s complete game, one-run masterpiece, but in game two, it was the O’s Mike Boddicker’s turn. He one-upped Hoyt with a complete game shutout. Game three was the complete opposite of games one and two, featuring 12 runs against the combined total of six through the first two games. The only problem for the White Sox was that 11 of those runs were scored by Baltimore. White Sox starter Richard Dotson allowed six runs in five innings, and the Sox bats weren’t able to help him out. The O’s put the icing on the cake with a four run ninth to put the game completely out of reach. This led the Sox into a do-or-die game four at Comiskey Park. A crowd of over 45,000 watched another true pitchers’ duel. Both teams were scoreless through all nine innings, but in the top of the tenth, the White Sox’s starter, Britt Burns, who was still in the game despite nearing 150 pitches, broke. He gave up one run, and when the Sox turned to the bullpen, Salomé Barojas couldn’t stop the tide. He allowed two more runs without recording an out before Juan Agosto and Dennis Lamp finally ended the threat. Baines led off the bottom of the tenth with a single, but that was all the Sox would get as the O’s took the series. The Orioles went on to win the World Series, and the White Sox went home.

‘83, like ‘77 is a season to remember. It was truly an exciting time for Sox fans, but mostly because the surrounding seasons were so dull. By the end of the eighties, the White Sox were back to looking more at their draft position than their playoff chances, rounding out a two decade stretch with only two especially notable years.

Speaking of two, remember when I said that there were two major developments in the eighties? I didn’t forget about that. Here’s the second one.

Its name is Jerry Reinsdorf.

Reinsdorf purchased the Chicago White Sox in 1981 from Bill Veeck after Veeck realized that he couldn’t compete financially in the free agent era. There is exactly one thing that you need to know about Jerry Reinsdorf. He loves money.

There is nothing on this earth more important to Jerry Reinsdorf than his money. He would no sooner surrender his money than he would surrender his heart, his soul, or his sacred memory of all that came before. His money tells the story of who he is, where he’s come from, and what he’s done.

As owner of the Sox, Reinsdorf would quickly develop a reputation as one of the most militant, anti-union, hard-line, and cheap owners in all of baseball.

Throughout their history, the White Sox have been defined at least partially by their enemies. At first, it was the Cubs, who opposed the Sox in their move to Chicago and in the 1906 World Series. Later, it was the Yankees, who denied the go-go era teams from making the World Series year after year. Now, the threat was coming from the inside.

It didn’t take long for Reinsdorf to start complaining about the state of Comiskey Park. By 1988, the beloved stadium had been neglected for some time, and was badly in need of either a repair or replacement. Reinsdorf was determined to have the taxpayers of Illinois foot the bill.

He made the terms extremely clear. If Springfield didn’t pass a tax increase to fund the new stadium, he would move the Sox out of town. He even had a destination picked out. In the late eighties, Tampa Bay was desperate for an MLB team. They were appealing to MLB for an expansion team or a relocation team. They offered Reinsdorf the new stadium he wanted, building the domed Tropicana Field before a deal was even struck. They offered him the tax breaks he wanted. Ever since the breakup of the go-go sox, Chicago had been thoroughly a Cubs town, and moving to Florida would let the Sox be the number one team, not just in their city, but in their State.

Reisndorf had set a deadline of midnight on June 1st, 1988.

On that day, debate carried on well into the night. Shortly before the deadline, with multiple votes still needed to pass the resolution, Representative John Dunn said "we can’t take care of the children, we can’t take care of the poor, we can’t take care of the sick, we can’t take care of the mentally ill. Let's shut this place down and go home and forget the White Sox.". After that quote, the midnight deadline passed.

The Chicago White Sox were dead. Long live the Tampa Bay White Sox.

Comments

Post a Comment