The History of the Chicago White Sox - Part 3

The 1919 World Series is forever known as the stage for one of the most famous scandals in the history of North American professional sports.

The Black Sox Scandal has left behind a complicated legacy in which it is extremely hard to separate fact from fiction. Much of public opinion today comes from the 1963 book and subsequent 1988 movie Eight Men Out, which told the story of the scandal. The book and movie have come under heavy scrutiny in recent years, accused of oversimplifying the events around the scandal and completely fabricating characters and events to create a more interesting story. The Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) created a book in 2015 called Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox that is a collection of papers attempting to set the record straight on a series of stories in and around the team. One of these papers, The Black Sox Scandal, is an attempt by writer Bill Lamb to tell the story of the scandal in as accurate terms as possible. This paper will be the main source for this entry.

One of the most important things to understand about the Black Sox Scandal was that it didn’t exist in isolation. Gamblers were constantly trying to convince players to throw games in the early days of baseball. The 1877 Louisville Grays featured four players who threw games for money from gamblers. A 1908 umpire refused a bribe to influence a late-season Cubs-Giants game. Multiple members of the 1917 Giants, the team that lost the World Series to the White Sox that year, were banned from baseball after repeated throwing allegations were made against them. Baseball was corrupt with gambling schemes from the start.

One of the biggest motivations for the scheme was, allegedly, the behavior of Charles Comiskey. Comiskey allegedly underpaid his players, was incredibly cheap around the margins for the team, and engaged in underhanded tactics to prevent players from reaching milestones that would trigger bonus payments. Much of this has been proven false. The SABR paper claims to have found payroll records showing that the White Sox players were well-compensated compared to the rest of MLB at the time.

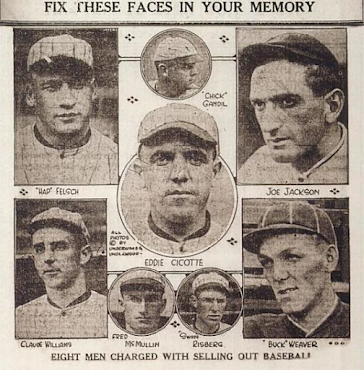

The SABR paper instead tells a story of division and factions in the White Sox clubhouse. One group was headed by Eddie Collins, the team’s captain. Collins was extremely well-educated and arrogant. Also on his side was Red Faber, known for his incredible performance in the 1917 World Series. The other group was the “rougher” group in the clubhouse. This second group consisted of Eddie Cicotte, Chick Gandil, Buck Weaver, Swede Risberg, Happy Felsch, and Fred McMullin. The SABR paper claims that “Envy, if not outright hatred, of the socially superior Collins” was a key motivator for the fix. Cicotte and Gandil were the players who contributed the most to the scheme, but they had plenty of help from both inside and outside the White Sox organization. A number of extremely well-connected gamblers assisted them, and gambling’s deep connections with baseball made the players sure that they could get away with it. Lefty Williams and Joe Jackson were later recruited to the group, bringing their total to eight players.

For six of them, their guilt is certain. Cicotte, Gandil, Risberg, Felsch, McMullin, and Williams are all remembered today as morally corrupt individuals who deserved their punishments. The real controversy comes from Buck Weaver and “Shoeless” Joe Jackson. These two players cannot be accused of throwing by any reasonable person. One look at the stats from the 1919 World Series showed that Weaver and Jackson played incredibly well. Jackson hit .375 in the series. Weaver hit .324. These numbers are good for second and third on the team. The only one who beats them is McMullin, who had a batting average of .500 in two at bats, a sample size small enough to disqualify his numbers. Jackson and Weaver were also second and third behind McMullin in OPS. There is a strong case to be made that, among players who received 10 or more at bats in the 1919 World Series, Jackson and Weaver had the best series of any player on either team. That, however, doesn’t matter. Jackson and Weaver were not disciplined for throwing the World Series. They were disciplined for knowing about the scheme, attending meetings, receiving payments, and not telling anyone about it. Their punishment was the same as the other six players involved in the scandal. All eight were banned from baseball for life.

Kenesaw Mountain Landis was appointed as the first ever Commissioner of Baseball in 1920 in order to respond to the Black Sox Scandal. Landis was given full power over both leagues in order to restore the faith of Americans in the competitive integrity of baseball. His decision to ban all eight players for life is to this day the harshest punishment ever given to a team in any single event in North American sports history. The punishment had the intended effect on baseball culture. Gambling schemes largely disappeared from the sport past this point, and to this day athletes gambling or being involved with gamblers is taken extremely seriously by all of the major American sports leagues.

From the White Sox’ perspective, it was as if the team train had crashed. Eight of the team’s best players were removed from the roster and the Sox received nothing in return. In only one year, the White Sox had gone from baseball royalty to universally shamed. The 1920 team went 96-58, good for second place in the American League. Cicotte, Gandil, Jackson, and the rest played the whole year as investigations went on in the background. In 1921, after Landis’s ruling, the Sox were 62-92, one of the worst teams in baseball. The White Sox were destroyed, and it would be a long, long, long time before they recovered.

Comments

Post a Comment